Archive

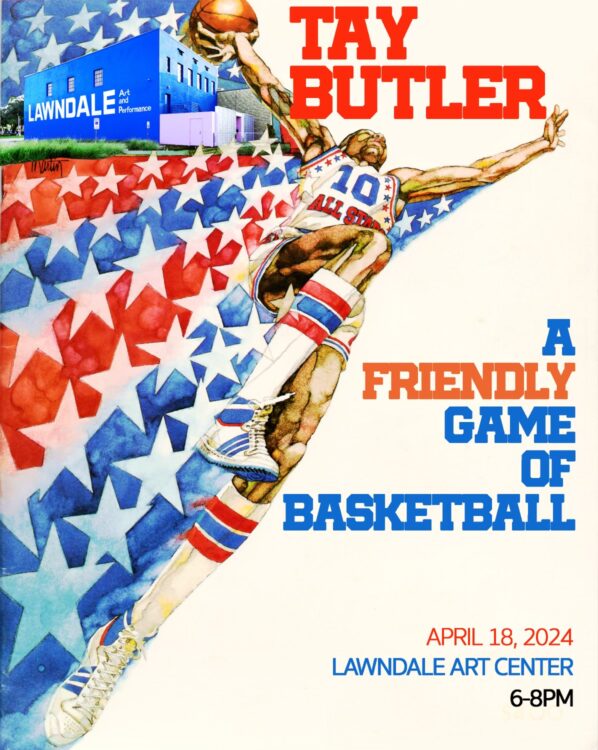

Tay Butler A Friendly Game of Basketball

About the Exhibition

A Friendly Game of Basketball in John M. O’Quinn Gallery is a solo exhibition by 2023/2024 Artist Studio Program participant Tay Butler. This multi-media exhibition presents Butler’s research of and art engagement with basketball’s racial history and contemporary anti-Black issues. Through various media—including installation, painting, drawing, photography, collage, music, and performance—Butler creates a multi-sensory environment which mirrors basketball’s pre-, post-, and in-game play.

Statement by the Artist & Writer

“‘The problem was “What shall we do with the Negro?…now the problem is “How can we get more of them?”’

Andrew Carnegie, Howard University, 1907.

“It is hard to argue against the opinion that basketball is king in the Black community. Difficult to assess or analyze statistically, it is something taken for granted. Both an ‘if you know, you know’ assumption within the community, and a well-worn stereotypical trope outside of the community. Teenagers and twenty-somethings maintain a connection to the game, either through direct play, or aesthetic cultural references. Middle-aged men who grew up playing the game, continuing as occasional ticket holders and coaches of children who play. Elders who ‘used to be a monster back in the day’, telling anyone who will listen how the game was so much better back when. All while the mouths of city governments, law enforcement, sneaker companies, non-profit founders, college coaches and scouts salivate. But what does it all REALLY mean?

“In 1891, Luther Gulick tasked his young assistant James Naismith with creating a game that could bring young, white boys back to Christianity. A game that could reverse years of ‘Victorian domesticity’ and promote manliness by utilizing physical fitness to enhance spirituality. This philosophical concept would become known as ‘muscular christianity’, and Naismith would fasten peach baskets to a beam randomly 10 feet high, merge the teamwork necessary in football, with the finesse and passing necessary other so-called primitive games, and ask players to toss a laced, leather ball into the basket. Several rule changes later, basketball was born.

“Today, basketball is one of the most popular sports in the world. As recently as 2022, The Fédération Internationale de Basketball, better known as FIBA, estimated worldwide players at 450 million. In American high schools, over 892,000 student athletes played. A whopping 55,498 student athletes played basketball for the NCAA that year. Even fewer make it to the pros, with 720 players playing at least one game in the NBA and WNBA during the 2022 season. These numbers are impressive, indicating a global game once thought incapable of replacing football or baseball in the hierarchy of American sports. Anywhere in America where Black people form a majority, the game is even more ubiquitous and suffocating. Arguably the biggest cultural force behind music and food, basketball has become a foundational pillar.

“In the sixteen years between its inception and when the first referee and spectator basketball game between all Black teams took place in Washington DC, basketball belonged to white society. Endorsed by President Theodore Roosevelt, a sport once thought ‘for sissies’ became useful, and universities, churches and athletic clubs created a world around it. Black teams were banned from the Amatuer Athletic Union and NCAA, while Black players were not eligible to play or coach against white teams in city leagues. Through the determination of Naismith’s only Black protege, John McLendon, and the actions of a handful of privileged and educated Black immigrants in New York and DC, basketball would slowly spread through a few small communities. It would not be until 1907 and after that basketball would become a tool for physical education, Black collaboration and collective economics. Today, the hold that basketball has on not just young, Black enthusiasts, but the imagined community as a whole, remains formidable. But lost in the frenzy of AAU tournaments, custom sneakers and celebration dances are the political ramifications of a sport now dominated by the Black body.

“In her book Black Scare/Red Scare, author and activist Dr. Charisse Burden-Stelly theorizes the merging of both Cold War era anti-communist paranoia and Jim Crow era fear of a Black rebellion with the consistent suppression of Black radical left and anti-capitalist politics. These new ideas were packaged as ‘American patriotism’, deeming anything in opposition as communism and therefore, anti-American. Any and all Black citizens could be reprimanded or worse for anti-Americanism, but the Black leaders, entertainers, athletes and celebrities would face a special kind of treatment. Basketball and its players, with its large stake in Black culture, would be no different.

“A Friendly Game of Basketball, a solo exhibition at Lawndale, finds Tay Butler concluding several years of research and art engagement surrounding the racial and political material within the sport. Comprising installation works, paintings, drawings, photography, collage, music and performance, viewers are welcomed into a multi-sensory environment mirroring elements of pre, post and in-game play. By taking the game and examining its historical archives and advertisements, identifying both its historical and contemporary anti-Black events, reintroducing the isolation and removal of its radical elements, and imagining a new application for the sport within the community, I am thinking critically about where the sport currently exists, and how it can do more to serve the community that loves it so much.”

-Tay Butler, Artist & Zora J Murff, Writer