Archive

Yumi Janairo Roth Detoured

Decorating Tips for Subverting Authority by Timothy Robert Rodgers, Ph.D. Chief Curator, Museum of Fine Arts, Santa Fe

What would an effective political intervention in the field of imagery be like?

T. J. Clark, an art historian sharpened by current world politics, rhetorically asked this question when he wrote about his latest group effort,Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War. He contended that world powers have created highly powerful and effective visual strategies for defining their positions: the destruction of the World Trade towers/ the night bombing of Baghdad, video confessions ofOsama bin Laden/ President Bush on the deck of a warship declaring victory, filmed beheadings ofAmericans/ digital photographs of torture at Abu Gharib. How can an artist intervene in these media spectacles without devolving into the well-worn theatrics of the horror film?

Yumi Janairo Roth suggests that perhaps the most effective strategy would be to start at the beginning:spotlight and then dismantle the visual language of authority and power that girds western society. This alphabet of authority has been carefully and thoroughly engrained into each of us. The orange highway cone; the police barrier; the broken white line; the solid white line all instantly convey their meaning and their threat. Do not cross, do cross. Do so here, do so here and risk your life. These signs promise safety and simultaneously threaten us with harm.

By marking our lived geography with the notions of safety and harm we set the stage for grand spectacles of terror. Inside the United States, in highly cultivated cities, in expensive skyscrapers, safety is almost guaranteed. And when such a safety zone becomes the site of intentional destruction we are horrified and dismayed, emotions tripled in strength because such destruction was not suppose to occur in this location, in this city, in this building. Once violated, all of our zones of safety become questionable and we struggle to regain a sense of security we thought could not be violated.

But safety can never be guaranteed, and it cannot inhabit a consistent space. It is a construction, like a building, that is carefully created and maintained. When the safety of a nation is threatened then so too is the authority of that nation. And it is for this reason that in times of war rulers create and promulgate grand spectacles of insurgence, liberation and victory. These spectacles not only serve to bolster the authority of the state but also to reassure the citizenry of their continued safety. Once safety is assured, then the language of authority that flows from the state becomes accepted and followed without thought.

This sense of complacency allows for the germination of the next spectacle of terror. Accepting and following without thought are the fertilizers that encourage growth in the fissures of a society. It is in this field that Roth attempts to intervene. Working with the everyday objects of authority–highway cones, police barriers, Jersey barriers, and safety glass–she transforms them by co-opting another language of safety: the decorative.

The end of the twentieth century witnessed an explosion of home decorating magazines all vying to define the decorative language of the home. Underlying the pictures and articles was the idea of the home as sanctuary, shelter that provided protection from the outside world. As a result, cocooning became a recognized verb that effectively implied the desire to insulate one’s self in soft (all natural, of course)cotton. But the cocoon, the home, had a much more elaborate language at play. The revival of 1960s and 1970s aesthetics, multicultural decorative gestures, a clean perfectionism, and thoughtful recycling of objects all became components of the “new” decorative language. This language, supposedly universal and timeless, also offered assurance of safety.

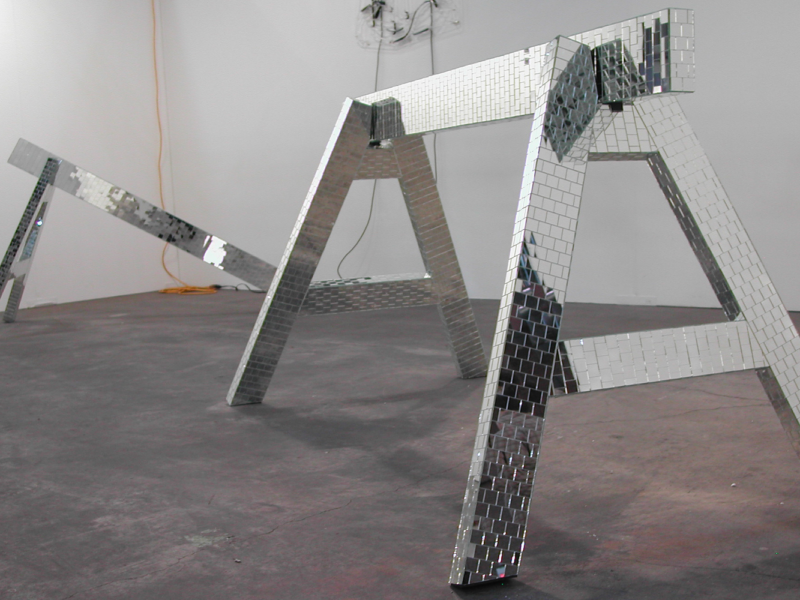

Two languages—one for authority and one for decoration—both offer what they cannot not guarantee:safety, ease and order. Roth recognized the falsity of the two languages and realized that by combining them in a single work she could destabilize both. Police barriers meticulously covered with disco mirrors a la Gucci; Jersey cement barriers beautifully draped in slip covers that Martha Stewart would covet; and highway cones transformed into piñatas that pay homage to the “diversity of our world,” these humorous and disturbing objects lay bare the mental numbness both languages create in exchange for their false promises.

Before the bombing of the Twin Towers, the intellectually challenging and disturbing nature of Roth’s sculpture was only partially experienced. Most viewers recognized the decorative language “misapplied”to objects of authority, and found the irony humorous. Some also lingered over the possible anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist implications of the work. Few, however, realized that by crossing the wires of decoration and authority, the sculptor offered critiques of both semiotic fields.

When cement barriers and police barricades began to sprout all over New York, international airports andIraq, everyone became aware of the limited degree of safety actually afforded by the objects. Instead they became as much signs for potential terror and instability as safety. And when the objects were misunderstood and/or violated we recognized the fragility of safety and the vast military/imperialist complex necessary to sustain it.

This fragility of safety lies at the heart of both decorative objects and those of authority. In the best of times, they almost dissolve into ideas of timelessness, universality, and neutrality. In the worst of times, and these are the worst of times, the massive imperialist agendas that support these ideas and objects becomes all too apparent and we quake at the implications. What Roth reminds us of, however, is that safety is never a reality, only a desire; that embellishments and flimsy objects cannot protect; and that the surface of the world is not a mirror of its hidden reality.

Artist Bio

Yumi Janairo Roth was born in Eugene, OR and raised in Chicago, IL and Reston, VA. She received her B.A. in anthropology from Tufts University and her B.F.A from the School for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. After a short stint of living in Chicago where she taught metalsmithing at Lill Street Studios, Yumi returned to graduate school and received her M.F.A. in metals from the State University of New York at New Paltz. Before moving to Boulder to teach sculpture at the University of Colorado, Yumi lived in Appleton, WI, a small Midwestern town known more for its cheese factories, local luminaries (Joe McCarthy and Harry Houdini), and paper mills than for its art scene. However, as a professor at a small liberal arts college, Lawrence University, Yumi made the most of it.

While in Appleton, Yumi shopped the Home Depot, Menards, and her local St. Vincent de Paul thriftstore for both materials and ideas creating sculptural wall and floor works that were a combination of construction grade materials, discarded domestic objects, and fine craftsmanship. Her most recent work continues to explore themes of ornamentation, domesticity, and humor, but also touches on ideas of authority and propaganda and how these arenas might overlap. The shift is evident in her modified police line barriers and traffic cones set up around urban, suburban and rural environments. She has exhibited her work in Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, New York, Milwaukee, Madison, Minneapolis, Mexico City, the Philippines and the Czech Republic. As Yumi continues to make work, she hopes to identify and explore the details of daily life that we have come to accept through routine living. Through this exploration of objects and materials, she hopes to reveal our complicity with and occasional longing for the everyday.